Read more about “The Queer Jubilee: 25 Years of Resistance,” a June 25 seminar led by Ramos and cosponsored by the American Academy in Rome.

Lucas René Ramos is the 2025 Jesse Howard Jr. Rome Prize Fellow in modern Italian studies and a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Columbia University. His research explores the entangled histories of gender, sexuality, and religion in modern Europe, with a focus on queer activism in postwar Italy. His dissertation, “Queer, Catholic, Communist: Forging a Sexual Revolution in the Italian Republic, 1958–1989,” traces how queer organizers navigated the influence of the Catholic Church and the political Left to build a movement for sexual liberation. At AAR, he is investigating the transnational networks that shaped Italy’s queer activism.

What first led you to investigate the unexpected intersections between Catholicism, leftist politics, and LGBTQ+ activism?

There is so much to connect within this trinity of knowledge-making, so I have to start with an anecdote. My connection to the Italian queer scene was fortuitous when I visited Rome in 2017 and met the Spanish artist Gonzalo Orquín. This trip was also my foray into doing oral history, which has informed many aspects of my research. Orquín made international news in 2013 for his exhibition Sì, quiero, which presented photographs of gay and lesbian couples kissing at Roman Catholic Church altars. The images compelled the Vatican to send Orquín a cease-and-desist letter. I was excited to meet him but felt an urge to bring these contemporary questions further back into our historical record.

My dissertation is a historical study of how the Roman Catholic Church impacted the coalition-building of queer grassroots organizers since the 1960s. I’ve traveled to seven cities in Italy and followed those discoveries to their international links in the Netherlands, US, and UK. Understanding queer history within these religious debates allows me to ask what compelled ex-priests to become radical gay revolutionaries, or why Leftist organizations discussed different ways to resist the “hetero-clerical-fascism” of Italian society. I realized that political Catholicism and sexuality had not been properly connected, let alone their overlaps with queer activists on the southern frontier of Europe.

As I write up my discoveries from my research trips and chats with fellows, I consistently come back to 2000 Resident David Kertzer’s first book, Comrades and Christians (1980), which offers me a framework to follow how religious, conservative, and radical tensions have engendered new forms of political mobilization. It’s been a pleasure at AAR to explore these questions further with Kertzer at teatime.

Have you found tension or congruence when comparing findings in your archival research with recollections from the gay and lesbian organizers you’ve interviewed?

I’ve had the privilege of interviewing with Italian activists of the lesbian, trans, and gay movements. As a historian who is constantly reading minutiae, I acknowledge that it is difficult for anyone to remember the specificities of organizing work from half a century ago. But because I’m also making activist histories visible, some for the first time, it’s essential that I maintain the integrity of these historical actors while still offering critique.

Whether or not I use oral interviews explicitly in my work, they have been invaluable. For example, Giovanna Olivieri of Rome’s Casa Internazionale delle Donne spoke at length with me about the types of organizing among lesbians who camped together in the early 1980s. I gained a better insight into their objectives, which are sometimes not clearly articulated.

Speaking of oral histories, I want to thank AAR curator-at-large Johanne Affricot for facilitating my meeting with trans activist Porpora Marcasciano, who participated in the AAR diversity initiative. In addition to learning from Porpora and her longtime friend and photographer Lina Pallotta, I brought Porpora to my studio to introduce the visual culture of my archive to her. We shared a laugh when I showed Porpora a photo that I thought depicted her, only to find out that it was of someone else she knew! This is one of many reasons why interviewing is useful.

How did your conceptions of the Academy change over the course of the fellowship?

The Academy has allowed me to make more connections in my field than I’d ever done before. I am grateful to have time and space to write my dissertation while also coming up with new projects. I am writing an article about queer activists responding to the 1979 Iranian Revolution, as well as another on the relationship between post-Fascist Catholic welfare services and queer and trans people’s healthcare access. I’ve received helpful feedback through the Academy’s works-in-progress meetings facilitated by Caroline Goodson, Andrew W. Mellon Humanities Professor.

Of course, my fellowship aligns with recent political events in Rome. As a modern Italianist studying the Church and queer life, I have seen the 2025 Jubilee celebrations that bring Catholic faithful to Rome. I also witnessed the Italian government ban surrogacy, which is a brutal jettisoning of gay, lesbian, and trans hopes for alternative family planning. Celebration and political unrest coexist, and this moment in history is motivating my research.

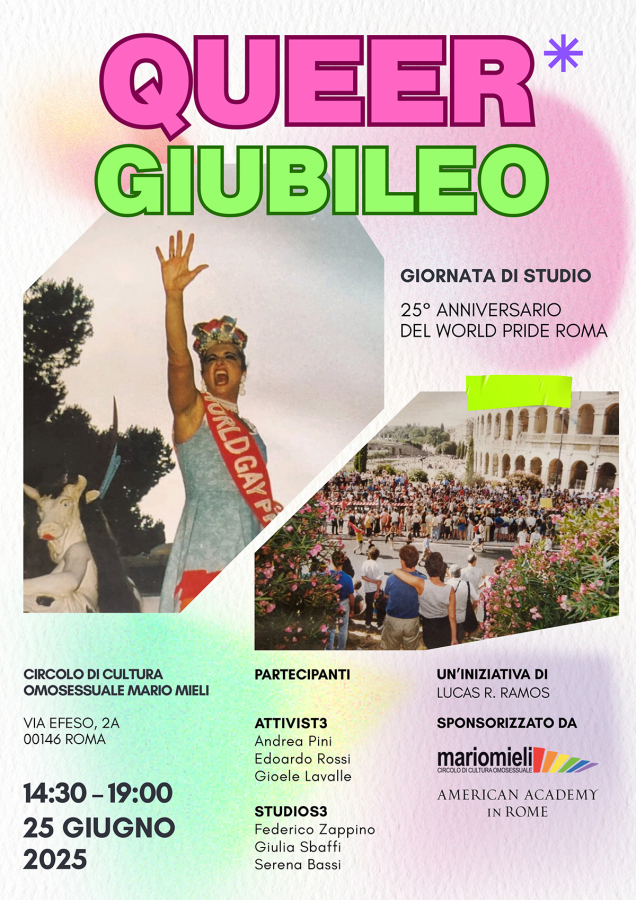

It just so happens that this year’s quarter-century Jubilee aligns with the anniversary of World Pride, a massive LGBTQIA+ demonstration that began in Rome to protest the 2000 Jubilee. Thanks to the American Academy, I feel less like a witness to these events: I am in the process of organizing a “giornata di studio,” or a day of study, in collaboration with the historic Roman homosexual movement, Circolo di Cultura Omosessuale “Mario Mieli.” We aim to bring activists and scholars together to discuss twenty-five years of protest in the new millennia.

What have you seen in the city of Rome that has made a strong impression on you?

Perhaps this is not something one sees but participates in: I am captivated by the Non una di meno movement in Rome. Members meet weekly for an assembly, seeking to end feminicide and transfeminicide in Italy. Their debates expand beyond the assembly. I often think about the unique role of the centro sociale (“social center”) in Italian recreational life, and how America doesn’t really have this. It’s a pleasure to walk down Corso Vittorio Emmanuele II, for example, and spot a poster for an event supporting an autonomist workers’ collective, where people discuss pressing contemporary political issues, followed by drinks. It is so easy to do this in Rome. On Via degli Orti di Trastevere, too, I always wondered why so many apartment buildings displayed Pride flags with the words PACE (PEACE), only to find out that the queer-inclusive Italian General Confederation of Labor had worked to create a row of affordable housing projects for low-income people. This is the urban landscape of Rome I’ve come to know and love.

How have your interactions with this year’s fellows and residents influenced your work or changed your perspective?

I have been immensely grateful for this year’s fellows—they are brilliant and supportive. Best of all have been impromptu moments. Devon Dikeou, upon hearing what I study, immediately picked out issue 21 of her zingmagazine from 2006–7 to share Tom Bianchi’s photographs of Fire Island in the 1980s. I am grateful for our deep and complicated chats about AIDS and shared community values. Likewise, Jenny Lin and I have discussed queer of color critique and the role of masculinity in our own archives. We’ve even done archival trips to the National Library together. Trained more broadly in the history of modern Europe, I benefit from talking with fellow historian Claire Dillon about debates in the field of Italian colonial studies, learning so much from her knowledge of Italian architectural history.

I’ve met fellows explicitly related to my research. The Italian Fellows this spring, the duo Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, curated an anthology on the first Italian homosexual revolutionary group, FUORI!, which is an acronym that translates as OUT!, as in “coming out” gay. This project was a part of the FUORI!-Gucci collaboration directed by Alessandro Michele in 2022. I had only ever read about that anthology, so I was delighted to talk with them about it. Meanwhile, visiting artist Eileen Olivieri asked me to collaborate on her work on Italian diaspora and abstraction. I wrote an essay, “Queer and Decolonial Belonging in Eileen Olivieri’s blue ghosts,” for a project she began at AAR.

It’s been a great fortune to collaborate with Selby Wynn Schwartz for our shoptalk, where we spoke on radical resistance and Italian queer politics. Neither of us realized how much of our current work was about the South—for her, mostly Taranto; for me, mostly Sicily. Her knowledge of Italian culture and contemporary politics has been instrumental to my research and, more simply, is an encouraging beacon of light to keep on writing.

Read more about “The Queer Jubilee: 25 Years of Resistance,” a June 25 seminar led by Ramos and cosponsored by the American Academy in Rome. The event will be held in Italian at the Circolo di Cultura Omosessuale Mario Mieli, located at Via Efeso 2A, 00146 Rome.